Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec ipsum neque, eleifend non rhoncus accumsan, volutpat in ligula. Class aptent taciti sociosqu ad litora torquent per conubia nostra, per inceptos himenaeos. Nulla sagittis justo vel felis lobortis, posuere cursus odio scelerisque. Maecenas et faucibus eros, ac volutpat velit. Proin ac augue vitae turpis semper vestibulum. Pellentesque non egestas justo. Nam accumsan convallis urna ac bibendum. Curabitur varius eleifend purus, non sollicitudin mauris maximus a. Integer urna augue, pellentesque nec turpis quis, auctor suscipit neque.

Continue reading “test blog post”Rocky Narrows

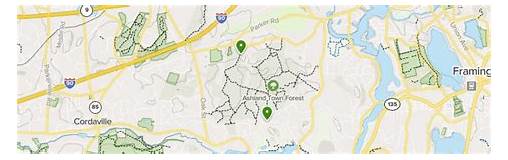

Sherborn MA Trails

The “Gates of the Charles.”

In 1897, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., acting as an acquisition agent for Augustus Hemenway, deeded to The Trustees 21 acres on the Charles River known as Rocky Narrows, the “Gates of the Charles.”

It became The Trustees’ first reservation, populated with a mixed forest of hardwoods and evergreens and 50-foot rock walls that date back 650 million years.

Today, visitors use an extensive trail system to explore Rocky Narrows and adjacent Sherborn Town Forest, and the setting showcases the 80-mile Charles River at its loveliest: a pastoral stream slowly moving between ancient cliff walls and steeply wooded hillsides.

In 1897, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., acting as an acquisition agent for Augustus Hemenway, deeded to The Trustees 21 acres on the Charles River known as Rocky

Ashland Town Forest & Cowassock Woods

Sudbury Valley Trustees

Ashland Town Forest & Cowassock Woods is a 660-acre parcel of open space located in Ashland and Framingham. This area has a natural wealth of granite outcroppings, upland and lowland swamp, vernal pools, mixed hardwood forest and several open pit quarries.

The Ashland Town Forest is managed by the Town Forest Committee (TFC). The Cowassock Woods is owned and managed by the (SVT).

Location and Access – The Ashland Town Forest and Cowassock Woods are located in the northeastern Ashland and southwestern Framingham. There is a 10-car parking lot on Winter Street by Harrington Drive and three small parking areas on Winter Street, Oak Street, Oregon Road and Salem End Road

Cedariver Trail

Millis MA

The Trustees of Reservation

Explore this former riverside farm along the carriage road loop or enjoy a leisurely paddle on the Charles.

Cedariver boasts beautiful frontage along the Charles River, and serves as a prime spot for paddlers to land their boats and take a hike. Situated within a river environment serving both as a wildlife corridor and as part of the Army Corps of Engineers’ flood-control efforts, Cedariver achieves multiple conservation goals, and its 55 acres add to Millis’ substantial web of protected public lands, conservation restrictions, and other open space.

Through Cedariver and other nearby reservations, you can explore more than 500 acres of Trustees-protected land along this section of the Charles River.

Idylbrook Conservation Land Loop

Medway Massachusetts

Discover this 1.6-mile loop trail near Medway, Massachusetts. Generally considered an easy route, it takes an average of 35 min to complete. This is a popular trail for birding, trail running, and walking, but you can still enjoy some solitude during quieter times of day. The trail is open year-round and is beautiful to visit anytime. Dogs are welcome but must be on a leash.

Wenakeaning Woods

Holliston, MA

Upper Charles Conservation Land Trust

Try this 1.6-mile loop trail near Holliston, Massachusetts. Generally considered an easy route, it takes an average of 35 min to complete. This trail is great for hiking, trail running, and walking. The trail is open year-round and is beautiful to visit anytime. Dogs are welcome, but must be on a leash.

Parking and access are on the east side of Summer Street (just north of the Wilde Buildiing), and on the west side of Highland Street off the side of the fire road that is just north of Timber Ledge Drive between the drivewaysato 1555 and 1557 Highland St.

There is off-road parking for several cars at each location.

Wenakeening Woods Trail Map

Garlic Mustard

Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is an invasive biennial weed. This article displays images to assist with identification and provides recommendations for control, including a management calendar and treatment and timing table.

Background

Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is an herbaceous member of the mustard family (Brassicaceae) brought over by early European colonizers. First documented in New York in 1868, it was used as a source of food and medicine. This plant’s biennial life cycle consists of a ground-level, or “basal,” year and a reproductive, or “bolt,” year. Garlic mustard’s vigorous reproduction has enabled it to spread from coast to coast, where it blankets habitats with moist, rich soils. A prolific seeder, it forms dense monocultures, leaving little room for native plants.

Description

Size: Less than 8 inches tall

Leaves: Kidney bean shaped, rounded teeth, and highly variable in size, each leaf is usually less than 4 inches across. The leaves form a basal rosette, meaning all the leaves emerge around a central, underground stem. Produce a garlic odor when crushed.

Leaves: Heart-shaped, each 2 to 4 inches across, with pointed, irregular teeth.

Flowers: Early in spring, clusters of four-petaled flowers emerge at the uppermost growing tip.

Fruit: By summer, the flowers are replaced by branched stems bearing the seed pods, or siliques. At first green, they become brown and brittle when ripe, a stage referred to as “seed shatter.” There is wide variability in silique size and exact number of pods. The individual seeds are tiny and brown, each less than ¼ inch long.

Garlic Mustard Look-alikes

Many native members of the mustard family, such as cut-leaf toothwort (Cardamine concatenata), also have cross-shaped white flowers with four petals. However, garlic mustard leaves are unique with their simple, kidney- or heart-shaped leaves in contrast to the compound leaves of the native species.

Dispersal

As an herbaceous biennial, it propagates solely through seed. In the spring of their second year, garlic mustard rosettes rapidly elongate their stems and produce a flowering head. Each plant will release many, sometimes thousands, of highly mobile seeds. Light enough to be carried by wind, they can also travel in water or by soil movement. The seeds also remain viable for long periods—over five years in optimal conditions.

Site

Suited to a wide range of habitat types, garlic mustard thrives especially well in areas with a disturbed overstory and basic soil pH. They are shade tolerant and will often spread from forest edges and openings to mature forest understories.

Control

Garlic mustard has a taproot, and unlike some invasive herbaceous perennials, it does not regenerate from root fragments. Therefore, this is one of the few invasive plant species that can be controlled manually by pulling. Manual operations that completely remove shoot tissue will prevent regrowth. Plants should be pulled before the seed shatter stage. Individuals hold their flowers for several weeks, giving the population staggered blooming periods. For this reason, it is a “best” practice to bag and remove pulled plants from the site, as even early pulling treatments probably include some plants that have viable seed.

Oriental Bittersweet

Background

Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) was introduced to the United States in the 1860s from east Asia. This woody, deciduous, perennial vine has since naturalized and become an extremely aggressive and damaging invader of natural areas. Oriental bittersweet chokes out desirable native plants by smothering them with its dense foliage and strangling stems and trunks. In some areas, it forms nearly continuous blankets along entire stretches of woodlands. Despite its aggressive nature and capacity to replace native plant communities, it is still sold and planted as an ornamental.

Description

Size

Single vines can reach 60 feet in length, though it will only grow as high as the vegetation it is climbing. As a perennial vine, it puts on yearly growth and can reach diameters of over 10 inches.

Leaves

Distinctly round with toothed edges, the leaves are alternately arranged along the stem and between 3 and 4 inches in length. In late summer the leaves turn vivid yellow, usually before native plants gain their fall color, making this vine easy to spot from a distance.

Flowers

Oriental bittersweet is dioecious; pollen and fruit are borne on separate male and female plants. In late spring, the female yellow-green flowers, each less than ½ inch long, grow from the leaf axils all along the stem in clusters of two or three. The male flowers are not distinct.

Fruit

Yellow-skinned fruit first appear on female plants in late summer. In fall the yellow skin splits to reveal a bright red center. The fruit is retained on the stem through winter. The conspicuous combination of yellow and red make Oriental bittersweet simple to identify even after leaf drop.

Stem

Young growth is bright green; larger stems have red-brown bark that has a cracked, fish-netted texture. The smooth stems do not have tendrils, barbs, or aerial rootlets since Oriental bittersweet climbs by twining or winding itself around host plants.

Look-alikes

American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) is a similar but far less common native species that is listed as rare or vulnerable in several states. American bittersweet leaves are more football shaped than rounded. Their flowers and fruit also emerge only from the ends of the stems, rather than at each leaf axil, as with Oriental bittersweet. The fruit of American bittersweet also has a bright red covering instead of yellow. While the two species do hybridize where they co-occur, American bittersweet is rare enough that the likelihood of an individual being the nonnative invasive species is high.

Autumn Olive

Autumn olive trees were planted for soil erosion. But its prolific fruit and seeds have disrupted native ecosystems.

Scientific Name: Elaeagnus umbellata

Introduction: Brought to U.S. from Asia in 1800s, planted widely in 1950s for erosion control.

Identification: Grayish green leaves with silvery scales bottom side, gives off shimmery look. Stems are speckled, often with thorns. Bell-shaped cream or yellow flower clusters. Silvery fruit ripens to red.

Edible? Yes, fruit can be eaten raw or made into jam.

What is the Autumn olive tree?

Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) is a deciduous shrub native to Asia that has spread as an invasive species throughout the United States. Introduced in 1830 as an ornamental plant that could provide habitat and food to wildlife, Autumn olive was widely planted by the Soil Conservation Service as erosion control near roads and on ridges.

Once thought as the best way to control erosion and provide wildlife habitat, it is now a major hassle. The plant’s positive attributes are quickly outweighed by its rapid and uncontrollable spread across forest edges, roadsides, meadows and grassland, where it displaces native plants.

Autumn olive can grow 20 feet tall and 30 feet wide. Its leaves are elliptically shaped and can be distinguished from other similar shrubs by the shimmery look of the silver scales found on its lower leaf surface. Autumn olive’s bell-shaped flowers are a cream or pale yellow color and bloom in early spring. They bring on red berries dotted with silver scales, which has led the plant to also be known as silverberry.

FRUIT OF THE AUTUMN OLIVE When mature, Autumn olive’s fruit is red and silvery specks. For this reason, the plant is also known as silverberry. © Lazaregagnidze via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Why is Autumn olive a problem?

Autumn olive is a problem because it outcompetes and displaces native plants. It does this by shading them out and by changing the chemistry of the soil around it, a process called allelopathy. Loss of native vegetation can have cascading effects throughout an ecosystem, and invasive species are one of the major drivers for a loss of biodiversity.

Autumn olive’s nitrogen-fixing root nodules allow the plant to grow in even the most unfavorable soils. Once it takes root, it is a prolific seed producer, creating 200,000 seeds from a single plant each year. Through fruit, birds will spread these seeds far and wide throughout pastures, along roadsides and near fences.

To make matters worse, attempts to remove the shrub by cutting and/or burning created even more autumn olive.

How could climate change make Autumn olive worse?

As the climate warms, resilient invasive species like Autumn olive can gain even more of a foothold over native plants. This plant takes advantage of changing seasons, leafing out early before native plants and keeping its foliage deep into the fall. By getting a head start, autumn olive can easily shade out other species.

Autumn olive can also use fire to its advantage. In both woodland and grassland areas, autumn olive can gain a foothold by sprouting faster than native plants after natural and human-managed fires. As climate change dries out more regions and enhances the risk of fire, hardy invasive plants like autumn olive could benefit.

LEAVES AND FRUIT Invasive Autumn olive in Ontario, Canada. The plant is best removed before it develops its seed-laden fruit, which can fall and germinate easily. ©

How to get rid of Autumn olive

Hand pulling autumn olive seedlings is an effective way to rid yourself of the plant.

Attempting to remove autumn olive by cutting or burning from your property can cause unwanted spreading as the shrub germinates easily.

Control efforts before fruiting will prevent the spread of seeds. If the plant is too big to pull, herbicides will be necessary to eradicate the plant from the general area of invasion.

You will need to cut and apply herbicide to the trunk repeatedly, from summer through winter. Please make sure to read and follow the directions on the herbicide label precisely.

You can also help by continuously being on the lookout for this pesky invasive species during hikes or walks through the neighborhood. For more information, see the USDA’s page about the plant.